28 Jan '26

After almost 50 years, the Dutch Sanctions Act 1977 (hereinafter: ‘the Sanctions Act 1977’) is in dire need of replacement. This is not surprising for a law dating from 1977, especially given the extremely complex nature of many international sanctions measures in 2026. On 23 October 2025, for example, the19th EU sanctions package against Russia was adopted. But that is just one example. EU sanctions often take effect very quickly, are often extensive and complex, and affect companies that are not always prepared for them. Hugo van Aardenne en Jikke Biermasz elaborate on the proposal for new sanctions legislation.

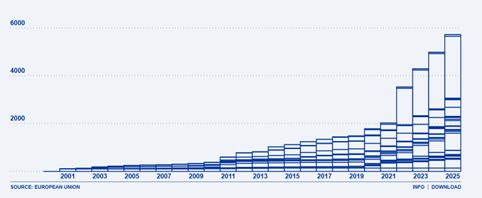

Nevertheless, sanctions are being used much more frequently.

Until now, this has meant in practice that sanctions in the Netherlands via UN resolutions and EU regulations fall within the scope of the Sanctions Act 1977, and violations of the Sanctions Act 1977 are punishable under the Dutch Economic Offences Act.

The Sanctions Act 1977 thus acts as a link between international and European sanctions and the national implementation of those measures. However, that link is now outdated.

In this context, a number of specific problems have been identified in the current enforcement of the increasingly complex sanctions measures under the Sanctions Act 1977.[1]

These include (1) missing or insufficient grounds for exchanging data, (2) the lack of the possibility to enforce sanctions violations under administrative law, (3) an inadequate system for management and administration, and (4) the need for market parties to gain insight into possible relationships with sanctioned persons and entities.[2]

To address these issues, the Sanctions Act 1977 is being almost entirely replaced by the "International Sanctions Measures Act" (‘Wet internationale sanctiemaatregelen’). In drafting the bill, the government was largely guided by a 2022 report by the National Coordinator for Sanctions Compliance and Enforcement (National Coordinator).[3] , we discuss the main points of that proposal and a number of important points from the December 2025 opinion of the Council of State on the bill, and you will see that international sanctions measures are a unique combination of international, European, criminal, administrative and civil law.

The explanatory memorandum to the bill emphasises the importance of effective information exchange for the enforcement of international sanctions. The enforcement of international sanctions is largely based on investigations into persons and entities associated with sanctioned persons and entities, with the primary aim of uncovering the ownership and control structures of sanctioned parties. It is therefore clear that information exchange is essential for proper compliance with international sanctions measures. However, because it cannot be taken for granted that international or European regulations automatically provide a sufficient basis for information exchange, a general basis is provided for in the bill (Article 8.2.5) on the advice of the National Coordinator.[4]

Criminal enforcement of the Sanctions Act 1977 is currently the starting point, with violations of the Sanctions Act 1977 being regarded as a form of financial and economic crime.[5] The Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Netherlands Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM) are responsible for supervising the administrative organisation and internal control of specific institutions, and there are also various supervisory authorities and implementing organisations involved in the implementation of the standards covered by the Sanctions Act 1977, but they do not have the administrative enforcement powers to enforce those standards.

The government has investigated the extent to which administrative fines and orders subject to a penalty for non-compliance could contribute to enforcement in the event of violations of sanctions. Following that investigation, the government concluded that administrative enforcement would be a useful addition for some of the sanctions.[6]

An important consideration is that criminal law has proven to be insufficiently 'proportionate' in cases of minor importance or where restoration should be the primary objective.[7] This does raise the question of whether cases have been dealt with under criminal law in recent years where the use of criminal law was not proportionate to the scale of the case or the seriousness of the offence.

In addition, this would allow scarce investigative resources to be better deployed for more serious cases, and the use of administrative law would increase the likelihood of detection and thus also the preventive effect. Incidentally, this is hardly substantiated.

The bill therefore offers the possibility of imposing an administrative order, an order subject to a penalty or an administrative fine for violations of sanctions.

So while the Netherlands is working on further broadening the administrative enforcement of sanctions rules, the European Union is moving in the opposite direction: across the EU, sanctions enforcement is being explicitly transferred to criminal law. The reason for this is that major differences in national enforcement practices undermine the effectiveness of EU sanctions measures.

This fragmentation prompted the EU to officially add the violation of EU sanctions measures to the list of EU offences within the meaning of Article 83(1) TFEU on 28 November 2022.[8] This established that sanctions violations are "a particularly serious form of crime with a cross-border dimension" and therefore require a harmonised criminal law approach.

Based on this decision, the EU was able to proceed with the adoption of a criminal law directive. This resulted in Directive (EU) 2024/1226, which contains minimum rules for criminalisation, definitions and maximum fines for violations of EU sanctions. Among other things, the directive stipulates that Member States must be able to impose prison sentences for intentional violations and that legal persons must be liable to fines of at least €40 million or 5% of their global annual turnover, depending on the category of offence. Member States must transpose these rules into national law by 20 May 2025 at the latest.

The Dutch government has indicated that the Netherlands does not need to amend its legislation, as existing criminal offences and penalty levels already meet the minimum requirements of the directive, according to the cabinet.

The bill currently envisages the following administrative bodies for the administrative enforcement of sanctions. These are Customs, the Investment Review Board (BTI) at the Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Financial Supervision Office (BFT) and a dean to be appointed (by decision of the general council of the Dutch Bar Association).[9]

The bill also provides a basis for designating other administrative bodies in the future, as it is impossible to predict what types of sanctions will be added in the future.

The bill for the International Sanctions Act provides a framework for the management and administration of companies affected by international and European sanctions. Dutch companies may be affected by sanctions against the ultimate beneficial owner, which in turn may lead to economic damage and undesirable social consequences. That framework is currently insufficient. In this context, the government points to the possible consequences of sanctions for employment and thus fundamental social rights, but also to the practical, financial and social problems that may arise in the maintenance and management of registered property affected by sanctions.[10]

Current sanctions regulations often provide for the possibility for the sanctioned party itself to request exemptions. This could include requesting the (partial) release of frozen assets. However, this is often only incidental and therefore does not provide a long-term solution to the problems that companies may face as a result of sanctions. A very practical example is the maintenance of and repairs to sanctioned goods. But there are many more practical and social consequences. The options available are only to a limited extent aimed at protecting the associated social interests.

However, because structural solutions would mean that the government would intervene in private companies in such situations, a legal basis would be required. The government therefore sought to regulate this in the bill. According to the Explanatory Memorandum, this also complies with the European Commission's recommendation to implement so-called 'firewalls'.[11]

In concrete terms, this would mean – if the proposal were to come into force in its current form – that it would be possible to sever the ties between the Dutch company and the sanctioned parent entity or the sanctioned natural person. The bill aims to achieve this by laying down the following provisions in the law:

The government has indicated that there will be a single central reporting point for citizens and companies that are required to report under sanctions regulations. Another related point is that market parties will be given greater insight by making greater use of the powers to make entries in public registers when sanctions regulations apply.

In December 2025, the Council of State issued its advice on this bill. We will discuss the main points of the advice below.

In its advice, the Council of State discusses the manner in which a general basis is provided for the exchange of information between administrative bodies and supervisory authorities with a role in the implementation of sanctions.[12] The general basis should then serve as a kind of safety net for situations where the EU regulation setting out the sanctioning measures does not provide sufficient regulation and the specific bases set out in the bill cannot be used either.

The Council of State points out that the provision of data under this bill may involve data that falls under the right to privacy as referred to in Article 10 of the Constitution. The Council of State therefore recommends that, in cases where the general basis is used, a bill be submitted as soon as possible to provide for the sharing of information in that specific circumstance.

In short, if information needs to be exchanged between administrative bodies or supervisory authorities in the implementation of sanctions and the general basis needs to be invoked, then, according to the Council of State, a bill must be submitted that provides a specific basis for that situation.[13]

The bill designates a number of specific administrative bodies, but it also provides for the possibility of designating other (as yet unspecified) administrative bodies with enforcement powers in the event of a sanction decision or sanction regulation. And although this is logical in itself – since it is impossible to predict in advance which penalty measures will apply in the future and which administrative bodies will then be most suitable – those administrative bodies will then also have far-reaching powers under this article (administrative order, order subject to a penalty and imposition of an administrative fine). The Council of State therefore recommends that the bill should stipulate that if this option is exercised, a bill should be submitted without delay to include the administrative body in question in this Act.[14]

The bill creates a framework for intervening in companies based in the Netherlands that are affected by sanctions. Specifically, the Minister of Economic Affairs may appoint an administrator ex officio if the sanctions lead to adverse consequences for the 'financial stability or continuity' of the Dutch company and thus 'may cause serious social, economic or employment effects for Dutch society'.[15] Incidentally, the management board and supervisory board of a company may also submit a request for the appointment of an administrator.[16]

Although the Council of State understands that, under the circumstances mentioned, the government wants to be able to intervene in companies affected by sanctions, it nevertheless strongly criticises the way in which the bill has currently regulated this.

This criticism is basically focused on the effectiveness of the measure. The government has been inspired by financial law and energy law.[17] However, according to the Council of State, there are (too) many differences between how this works in financial and energy law and how it would work under the International Sanctions Act. For example, the Council of State argues that there is already a great deal of supervision in the financial and energy sectors and that companies in those sectors are therefore (in a sense) accustomed to that supervision. International sanctions, on the other hand, can also affect companies and sectors that are much less accustomed to regulators. Moreover, the proposed measure is not a last resort but the only means of intervention.[18]

A second difference pointed out by the Council of State is that, under existing sectoral legislation, the administrator can replace the director or the board.[19] This raises the question of whether the administrator would not be placed in an impossible position, particularly in a situation where intervention would be required and the existing board is unable or unwilling to take measures.[20]

A third difference pointed out by the Council of State is that, unlike existing sectoral legislation, many companies that would be affected by the new International Sanctions Measures Act operate on the basis of agreements. And many business agreements and agreements used to finance companies include provisions stating that a resolutive clause will take effect if there is a change in ownership or control within a company. In that case, the appointment of an administrator could have direct consequences for the financing of a company that is (already) affected by sanctions. According to the Council of State, too little attention has been paid to the proposed measure of the administrator, particularly with regard to these points.[21] This is especially true given that these are often not failing companies, but companies affected by international sanctions as a result of political conflict.[22] Furthermore, insufficient consideration has been given to the possibility that intervention in Dutch companies could also have international (political) consequences. All in all, the Council of State wonders whether the proposed measure can actually be used effectively in practice.

We find it particularly interesting that the Council of State explicitly refers to the possibility of the inquiry procedure at the Enterprise Chamber of the Amsterdam Court of Appeal.[23] This is particularly relevant in cases where intervention is required at a company affected by sanctions. It is noteworthy that the Council of State also explicitly refers to the Nexperia case, in which the court ruled on a petition within four hours.[24] [25] According to the Council of State, this procedure offers many opportunities to call to order directors of companies who neglect the interests of the company, but this should also be possible when the public interest is at stake. The Council of State also recommends including the possibility of this procedure in the bill and suggests giving the Minister of Economic Affairs direct access to this procedure. The Council of State does not comment on whether the Enterprise Chamber would also be able to anticipate the international political consequences. This was previously part of the criticism of the administrator's remedy. In any case, this clearly shows how incredibly complex the regulations surrounding the implementation of sanctions are in practice.

It will be interesting to see to what extent the (new) government will amend the bill before it is sent to the House of Commons for substantive debate. We will, of course, be keeping a close eye on these developments. If you have any questions about what this will mean for your company, please do not hesitate to contact us.

This article was written by Hugo van Aardenne and Jikke Biermasz, solicitors at Ploum. Ploum has a dedicated team of specialists with extensive expertise in customs, export control and sanctions law. The team advises and litigates on a daily basis on complex issues at the intersection of administrative, civil and criminal law. Thanks to this integrated approach, clients can count on practical, strategic and legally in-depth support in the enforcement of and compliance with European and international sanctions regimes.

[1] Explanatory memorandum, p. 3.

[2] Explanatory memorandum, p. 3.

[3] Report by the National Coordinator for Sanctions Compliance and Enforcement, 15 May 2022.

[4] Explanatory memorandum, § 3.6, pp. 31 and 32.

[5] Explanatory memorandum, § 3.2, p. 10.

[6] Explanatory memorandum, § 3.2, p. 10.

[7] Explanatory memorandum, § 3.2, p. 11.

[8] Via Council Decision (EU) 2022/2332.

[9] Explanatory memorandum, § 3.2, p. 11.

[10] Explanatory memorandum, § 3.4, p. 16.

[11] Explanatory memorandum, § 3.2, p. 16.

[12] Article 8.2.5 of the Bill on international sanctions measures.

[13] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 10.

[14] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 11.

[15] Article 5.3 of the International Sanctions Measures Bill.

[16] Article 5.5 of the Bill on International Sanctions Measures.

[17] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 5.

[18] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 6.

[19] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 6.

[20] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 6.

[21] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 6.

[22] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, pp. 6 and 7.

[23] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, pp. 7 and 8.

[24] Opinion of the Council of State on the International Sanctions Measures Act, 3 December 2025, W02.25.00209/II, p. 8.

[25] See also ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2025:2738, among others.

Contact

28 Jan 26

19 Jan 26

15 Jan 26

13 Jan 26

13 Jan 26

05 Jan 26

31 Dec 25

31 Dec 25

22 Dec 25

16 Dec 25

15 Dec 25

15 Dec 25

Met uw inschrijving blijft u op de hoogte van de laatste juridische ontwikkelingen op dit gebied. Vul hieronder uw gegevens in om per e-mail op te hoogte te blijven.

Stay up to date with the latest legal developments in your sector. Fill in your personal details below to receive invitations to events and legal updates that matches your interest.

Follow what you find interesting

Receive recommendations based on your interests

{phrase:advantage_3}

{phrase:advantage_4}

We ask for your first name and last name so we can use this information when you register for a Ploum event or a Ploum academy.

A password will automatically be created for you. As soon as your account has been created you will receive this password in a welcome e-mail. You can use it to log in immediately. If you wish, you can also change this password yourself via the password forgotten function.